The History of Asheville's McCormick Field Speedway

- Heath Towson

- Jul 28, 2024

- 12 min read

Racer Banjo Matthews in "Mr. X" crossing the finish at McCormick Field Speedway

Come along with us on this month's historical journey through Asheville's motoring history as we take a glimpse into competitive motorsports in the city! Did you know there was a brief break in baseball so that racing could take over our local baseball stadium? More and more of Asheville's racing history continues to be revealed as more racers are sharing their stories of the Golden Era of motorsports in the city. Now that we know racers were roaring around this little stadium, it's hard to not try to imagine the sound of V8s echoing through the walls when we are at a Tourist game!

McCormick Field and Memorial Stadium (top), courtesy of the Ball Photo Collection, UNCA Special Collections

McCormick Field has long been known as the home of the Asheville Tourists Baseball Team. The field was constructed in 1924, as part of Asheville’s master plan for revitalization under Mayor John Cathey, using a city master plan designed by noted city planner, John Nolen. It was named for Dr. Lewis McCormick, the city’s only bacteriologist, who started the “Swat That Fly” campaign in 1905, in order to reduce the city’s burgeoning problem with houseflies transmitting disease. McCormick reportedly paid children a nickel for each dead fly they brought to him.

Professional baseball in Asheville dates back to 1897, with a team called the Moonshiners. The name was changed to the Asheville Skylanders and later the Asheville Tourists, somewhere around 1915. Throughout the history of the team, there would be several disruptions to Tourists baseball in Asheville. While World War II was raging across the globe, Asheville had no white minor league team from 1943 to 1945. The segregated Asheville Black Tourists and Asheville Blues continued to play pro baseball in the Negro League until 1946. By 1955, the Tourists were one of just four teams left in the Tri-State League. The Tri-State league was described by some as “a fly by night operation” and folded by the end of the 1955 season. Longtime Asheville Citizen-Times reporter Bob Terrell noted that attendance had been steadily declining for years.

With no baseball team and an absent fan base, the city owned facility had to do something to keep the park open and to be able to pay their bills. The stadium was leased to a North Wilkesboro businessman named Jim Lowe in 1956, who would turn it into a NASCAR short race track called McCormick Field Speedway. James Lucius Lowe, known as “Jim” was the son of Lucius Lowe, the founder of Lowe’s Hardware in Wilkesboro, North Carolina. Lowe was a WWII veteran and after serving in the war, sold his interest in Lowe’s Hardware to his brother in law, Carl Buchanan Jr. After selling his hardware interest, Jim Lowe founded Lowe’s Foods in 1952: a North Carolina grocery chain with branches in several states. After selling Lowe’s foods, Lowe dabbled in other Wilkesboro businesses including B and L Cadillac-Oldsmobile dealership, Wilkes Bowling Lanes and The Rollercade in North Wilkesboro.

Local racer Ed Cox, Jack Pike scrapbook

Lowe had a lot of work ahead of him to transform McCormick Field from a baseball stadium into a NASCAR track. He started by paving a quarter mile oval track around the perimeter of the baseball diamond. To transform the rest of the 32 year old stadium, Lowe and his race director, C.F. Powell started construction and renovation on multiple pieces of the ballpark. In addition to paving an oval around the baseball diamond, the high bank behind the stadium known as Hunt Hill was dug back for more seating and a protective fence for spectators. The race pits were placed just behind the track wall, beyond the third base bleachers.

In addition to the improvements to the stands, new bleacher seats were dug into the bank all the way to the left field fence, below Memorial Stadium. At the time of opening, the Asheville Citizen-Times stated that the park would seat 8,000 fans and if there were larger crowds, it could be stretched to a 10,000 person capacity. For additional safety of the spectators, large metal fencing was erected behind home plate and portable walls were constructed to be placed in front of the dugouts, which were said to be removable for baseball games. Little if any baseball was played while the stadium was a race track.

In addition to McCormick Field being transformed into a race track, several other sports stadiums around the country would make the same transition. When NASCAR was first organized in late 1947, there was not an abundance of purpose-built tracks around the country. Many of the early tracks were at local fairgrounds, which served many purposes. As the sport grew with the construction of the superspeedway at Darlington, NASCAR continued to search for venues that offered permanent seating and spectator comfort. NASCAR found a home at Bowman Gray Stadium in Winston Salem, North Carolina in 1950. It has a quarter mile track in the football stadium that hosted 29 cup series races from 1958 to 1971. Soldier Field in Chicago was also famous for auto racing before it became the home for the Chicago Bears. It hosted competitions for “Hot Rods” and Midget class racing cars.

McCormick Field Speedway opened to the public on June 16th, 1956. McCormick Field Speedway became a featured track on the NASCAR circuit in the Sportsman class. The first race featured 125 laps of Sportsman and amateur racing, bringing along some of NASCAR’s top racers. Ralph Moody (co-founder of Holman-Moody racing with John Holman) from Dania Beach, Florida, local Asheville legend Banjo Matthews and Dink Widenhouse of Concord were in the field for this warm summer night race.

Other NASCAR notables who raced at McCormick Field included Junior Johnson, Ralph Earnhardt, Curtis Turner, Fireball Roberts and Joe Lee Johnson became common names at many of these races in Asheville. McCormick Field Speedway provided much entertainment for the city, especially during this seminal period for the growth of the NASCAR organization. Admission was normally $2 per person, although the speedway hosted a “Ladies Night” once a month, where ladies were admitted for free. There was also a “Powder Puff Derby,” where women would drive their husband’s cars for a 10 or 20 lap race in between NASCAR Sportsman car races. This was typically done between race heats as a gimmick to increase attendance.

How cars got to the track - Jack Pike's "Poison Love II" Race car

McCormick Field Speedway built several local racers up into legendary status. Several of these local racers were Banjo Matthews, Dickie Plemmons and Ed Cox. One of the most prolific racers of McCormick Field Speedway was Edwin “Banjo” Matthews. Matthews earned the nickname “Banjo” from his gold wire rimmed glasses with thick lenses that looked like a banjo instrument. In 1952, a 20 year old Matthews packed up his 1939 Mercury Club Coupe with everything he owned, along with his wife and daughter and made the journey from Miami, Florida to the Carolinas to be closer to the burgeoning NASCAR racing circuit. With an old Snap On toolbox filled with not many tools, Banjo had some mild success in the 1952 Southern 500 at Darlington raceway in South Carolina, finishing fifth.

Banjo would end up settling in Asheville and set out to open his own race shop. He went to several local banks asking for a $500 loan, which was not granted to him. He ended up driving for Eddie Joyner and Toy Jones, who had a race team and auto shop out on Brevard Road. Eddie Joyner was an Asheville local who owned the Eddie Joyner Speed Shop, selling hot rod speed equipment manufactured in California to Asheville bootleggers, hot rodders and racers. Toy Jones was one of the area's best engine builders, known for building some of the most powerful Ford “Flathead” V8 engines. The cheap and plentiful Ford Flathead engine would become the most common engine in race cars of this era.

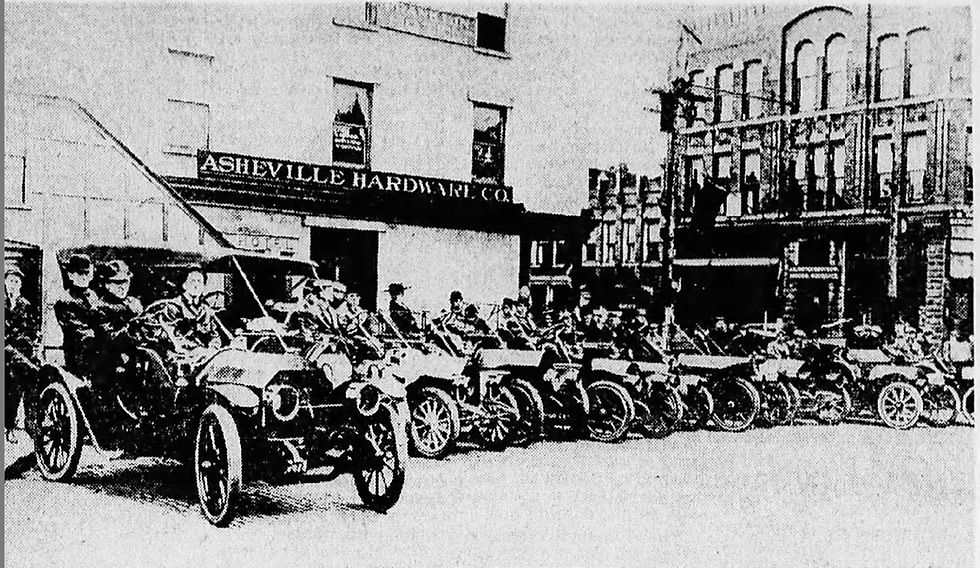

Racers on track - Jack Pike photo album

While driving for Joyner and Jones, Banjo counted himself among two other teammates. Local racer Dickie Plemmons and Harry Clay, who all drove for Joyner and Jones’ racing team. Rather than have racing numbers painted on their cars, each of these racers went by a letter on their car. Banjo’s car was known as “Mr. X” while Plemmons and Clay would alternate between “Mr. Y and Mr. Z.”

Banjo became so dominant racing at McCormick Field, all sorts of stunts were pulled by racing promoters to stop his winning streak. In one race, Banjo was placed at the back of a 36 car field and his car was turned around facing the opposite direction of all the other racers. He ended up catching up and winning the race anyway. In other races, a bounty was put on him by the race promoter for anyone who could knock him out of the race.

In one race, Banjo Matthews was fined $50 by NASCAR for ramming Ralph Earnhardt at McCormick Field Speedway. He was quoted as saying “It all occurred in the heat of the moment and while I feel Earnhardt was as much at fault as I, I plan to go ahead and pay the fine. I deserved it.” The two racers had gotten caught up in a skirmish and Earnhardt’s car was knocked into the first base dugout, later having to be towed out. Cars crashing into the dugouts would become somewhat commonplace.

Racers sped around the quarter mile track between 49 and 60 miles an hour or so. Because the track had very short straightaways and sharp turns, it was not known for top speed like today’s modern speedways, where speeds can reach close to 200 miles per hour. The track record of circling the speedway stood at 16.43 seconds for a long time. These homemade race cars would have made a glorious noise, echoing off Hunt Hill behind the stadium with their unmuffled, high compression V8 engines screaming in anger. The noise of thousands of fans yelling for their favorite driver as gasoline vapors wafted over the bright stadium lights would have been quite an experience.

Banjo Matthews in the shop, Photo courtesy of Jack Pike

Not everyone in Asheville was a fan of the McCormick Field Speedway. Several letters written to the editor of the Asheville Citizen-Times complained of noise and smoke, while others were greatly in favor of the local track. Shortly after the track opened, 136 residents of the Five Points neighborhood gathered together to hire an attorney and sign a petition to stop racing and return baseball to McCormick Field.

In response to this complaint, Mrs. D.E. Peebles living at 8 La Rue Street wrote a letter to the editor of the Asheville Citizen-Times stating the following:

“This is in reference to the 136 residents who have signed a petition to stop Stock Car Races at McCormick Field. It seems that regardless of what kind of entertainment - whether it be for children, adults or both is brought to Asheville there are always a few people who object to its presence in our city. In this case, the main excuse is “we are saving McCormick Field for baseball.” Well, if we haven’t had our chance at baseball since McCormick Field was erected in the twenties, I think it is time to give up and put the field to better use.

The petition complained of “terrible noises” and said the races produced more noise in one night that ten years of baseball and football in both parks (Memorial Stadium). The reason for this could be that there have hardly been 4,000 fans all totaled in ten years of baseball at McCormick Field. The people living in the vicinity of McCormick Field should be immune to the noise of squeaking and squawling of tires since they hear it seven nights a week at drive-in restaurants near-by. The attorney for these 136 residents said, “the noise of 4,000 people begging racing maniacs to kill themselves” was disturbing to the neighborhood. I think if this attorney and the people opposing these races would give their support to the law enforcement officers and try to break up this speeding on the highways and drag racing (just to name two illegal “entertainments”) that stock car racing - as legal an entertainment as there is would be enjoyed by the majority of the residents of Buncombe and surrounding counties. “

Mrs. Peebles is making reference with “squealing tires and illegal racing” to both the Southland and Five Points drive in restaurants, where many residents of the historically Black neighborhoods of Southside and Five Points would meet up to street race on Southside avenue and modern day South Charlotte street.

NASCAR Convertible Series Race - Courtesy of Smyle Media

In its first year of operation, McCormick Field Raceway produced a profit, something the Asheville Tourists baseball team had not ever been able to achieve. For many years, the Asheville Tourists baseball organization had been operating on a deficit budget. The deficit would be subsidized by the city of Asheville, who owned the ballpark. After the first season of racing, the Asheville Citizen-Times reported on November 6, 1956 that McCormick Field Speedway had netted a profit of $9,677.17 (around $110,557.27 in 2024 dollars). During this first year of operation, the track grossed ticket sales of $73,247 (around $836,813.68 in 2024 dollars) in only a partial racing season.

McCormick Field Speedway not only hosted NASCAR races and midget race cars, but also foreign sports car racing time trial events through the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA). Many of these races would attract over 100 sports cars to compete against the clock as they raced around the NASCAR track in time trials. Many of these events were organized by local attorney and sports car dealer Herschel Harkins. Harkins’ owned the foreign car dealer, Manor Motors, selling Fiat, Jaguar, Austin Healey and MG at 192 Coxe avenue. Harkins was a fixture in the foreign sports car enthusiast scene and in addition to organizing events at McCormick Field, organized the inaugural Chimney Rock Sports Car Hill Climb.

Preparation for SCCA Race - Herschel Harkins Collection

During one of these SCCA time trials, a special celebrity guest appeared. While Robert Mitchum was in Asheville filming the classic, Thunder Road in the fall of 1957, he was invited as an honorary field judge. Mitchum was also known as a car guy and owned a Jaguar XK120 sports car. Local legend has it that his son, Jim Mitchum burst through the gates at the back of McCormick Field and sped around the track in the star car of Thunder Road, character Lucas Doolin’s 1951 Ford. Jim Mitchum was kicked out of the event for his antics, which angered Robert Mitchum, who also left the event.

By 1959, the city of Asheville was ready for baseball to and was beginning to revive the Asheville Tourists team by enrolling in a new league. Jim Lowe had signed a six year lease agreement with the city of Asheville, which they decided to break in February of 1959 before McCormick Field’s 4th season of racing could begin. Lowe’s company, McCormick Field Speedway Inc. surrendered the lease and the city of Asheville forgave $10,000 of rent that was due from 1958. The Asheville’s tourists had joined the Class A league and the city wanted to begin the process of returning McCormick Field back to a baseball stadium.

City Manager J. Weldon Weir announced that Lowe’s company had invested around $27,000 in the field and its facilities in 1956, which the city planned to amortize repayment of over a six year period. Weir said in a statement to the Asheville Citizen-Times that the asphalt on the quarter mile race track would be utilized in paving an area behind third base and left field, the section which was the pit area for race cars. The stadium planned to cut a new entrance from Hunt Hill behind the stadium where they could add more parking for another 100 cars. The corporation that owned and managed the Tourist’s baseball club, Community Baseball Inc. had also considered renting these new parking spaces to holders of box seats.

Over its three years of operation McCormick Field was fairly successful for generating income. In 1956, tickets grossed $73,247 and in 1957, $66,410. The Asheville Citizen-Times was not able to report gross sales for 1958, but it was said that the speedway lost money this year. 1958 was also a nationwide economic recession, which could have also hurt sales. By 1958, admission had risen to $3 per person, which equates to around $35 a ticket in 2024 dollars, more expensive than Tourist tickets at the time of this writing, which start at $9.

The city’s agreement with McCormick Field Raceway under the terms of their lease was to receive $6,000 or 15% of the gross ticket sales in the first year, and $10,000 or 15% of the gross for the following five years. The city’s share the first year of racing in 1956 was $9,677. In 1957, the 15% percent figure fell $39 short of the $10,000, so the racing group wrote a check for $10,000.

When the city closed McCormick Field Speedway, the golden era of NASCAR was starting to begin in Asheville and the rest of the South. McCormick Field had led to a rich beginning for the sport. The much larger Asheville-Weaverville racetrack north of the city was still in operation and soon, the New Asheville Motor Speedway at Carrier Field would be constructed in 1962. We plan to write about both of these racetracks as well and their importance to NASCAR history as well!

Want to wear a piece of Asheville's automotive history? Grab one of our McCormick Field Speedway T-Shirts in the MMT Shop! McCormick Field Speedway T-Shirt | My Site (mountaineermotortours.com)

Sources:

Newspaper Articles:

Asheville Citizen-Times. (May 11, 1958). McCormick Field - Plemmons Wreck . Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 17, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-mccormick-field/151510541/

Asheville Citizen-Times. (May 18, 1957). McCormick Field Convertible races. Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-mccormick-field/117292916/

Asheville Citizen-Times. (April 26, 1958). McCormick Field Racers. Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-mccormick-field/117292879/

Asheville Citizen-Times. (August 2, 1992). McCormick Field Racing. Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-mccormick-field/120298166/

Asheville Citizen-Times. (April 12, 1959). Closure of McCormick Field Raceway. Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-closure-of-mccor/151969676/

Asheville Citizen-Times. (April 20, 1958). Banjo 1958 McCormick Field Line Up. Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-banjo-1958-mccor/151970302/

The Asheville Times, February 18, 1959, Page 1. via Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-asheville-times-mccormick-field-race/151969755/ : accessed July 28, 2024), clip page for McCormick Field Raceway Closure by user towsonhe

Asheville Citizen-Times. (August 22, 1957). Powder Puff Racing McCormick Field. Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-powder-puff-raci/120381635/

Asheville Citizen-Times. (November 6, 1956). McCormick Field Raceway - Net Profits 1956. Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-mccormick-field/151553962/

Winston-Salem Journal. (June 16, 1956). McCormick Field Speedway Opening. Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/winston-salem-journal-mccormick-field-sp/151554015/

Asheville Citizen-Times. (July 14, 1974) A Toolbox and a Dream, Bob Terrell

Websites:

.jpg)

Comments